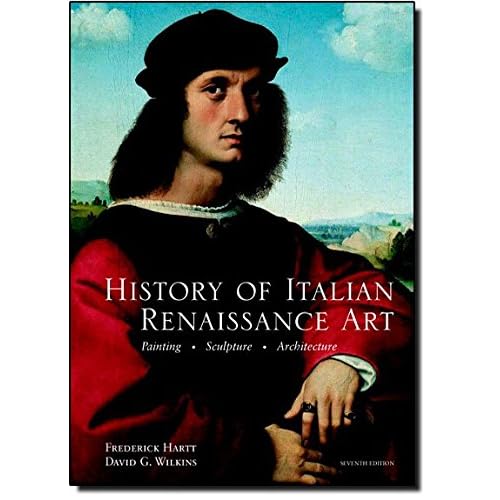

History of Italian Renaissance Art, 7th Edition

Category: Books,Literature & Fiction,History & Criticism

History of Italian Renaissance Art, 7th Edition Details

From the Back Cover For survey courses in Italian Renaissance art. "A broad survey of art and architecture in Italy between c. 1250 and 1600, this book approaches the works from the point of view of the artist as individual creator and as an expression of the city within which the artist was working." "History of Italian Renaissance Art," Seventh Edition, brings you an updated understanding of this pivotal period as it incorporates new research and current art historical thinking, while also maintaining the integrity of the story that Frederick Hartt first told so enthusiastically many years ago. Choosing to retain Frederick Hartt's traditional framework, David Wilkins' incisive revisions keep the book fresh and up-to-date. Read more About the Author The late Frederick Hartt was one of the most distinguished art historians of the twentieth century. A student of Berenson, Schapiro, and Friedlaender, he taught for more than fifty years, influencing generations of Renaissance scholars. At the time of his death he was Paul Goodloe McIntire Professor Emeritus of the History of Art at the University of Virginia. He was a Knight of the Crown of Italy, a Knight Officer of the Order of Merit of the Italian Republic, an honorary citizen of Florence, and an honorary member of the Academy of the Arts of Design, Florence, a society whose charter members included Michelangelo and the Grand Duke Cosimo I de' Medici. Hartt authored, among other works, Florentine Art under Fire (1949); Botticelli (1952); Giulio Romano (1958); Love in Baroque Art (1964); The Chapel of the Cardinal of Portugal (1964); three volumes on the painting, sculpture, and drawings of Michelangelo (1964, 1969, 1971); Donatello, Prophet of Modern Vision (1974); Michelangelo's Three Pietàs (1975); and the monumental Art: A History o f Painting, Sculpture, Architecture, now in its fourth edition (1993). David G . Wilkins is professor emeritus of the history of art and architecture at the University of Pittsburgh and former chair of the department. He has also served on the faculties of the University of Michigan in Florence and the Semester at Sea Program. He is author of Donatello (1984, with Bonnie A. Bennett); Maso di Banco: A Florentine Artist of the Early Trecento (1985); The Illustrated Bartsch: "Pre-Rembrandt Etchers," vol. 53 (1985, with Kahren Arbitman); A History o f the Duquesne Club (1989, with Mark Brown and Lu Donnelly); Art Past/Art Present, a broad survey of the history of art (fifth edition, 2005, with Bernard Schultz and Katheryn M. Linduff); and The Art of the Duquesne Club (2001). He was the revising author for the fourth and fifth editions of History of Italian Renaissance Art: Painting, Sculpture, and Architecture (1994, 2003) and co-editor of The Search for a Patron in the Middle Ages and the Renaissance (1996, with Rebecca L. Wilkins) and Beyond Isabella: Secular Women Patrons of Art in Renaissance Italy (2001 with Sheryl E. Reiss). He was editor of The Collins Big Book of Art (2005). In 2005 he also received the College Art Association’s national award for Distinguished Teaching in Art History. Read more

Reviews

This is a sweeping and magnificent history of Italian Renaissance art from about A.D.1260 to 1600. Frederick Hartt was one of the greatest art historians of the 20th century. During WWII, He served in the United States Army as one of the Monuments Men, documenting and protecting works of art hidden from the Nazis. Florence made him an honorary citizen. Professor Hartt died in 1991. This 7th edition has been updated by David G. Wilkins, recipient of the College of Art Association's national award for the Distinguished Teaching of Art History.In this 736-page book, almost all of the artwork is in gorgeous colors. The writing is informative, easy-to-read, and engaging. All technical terms are clearly explained. It makes a great reference book, or a helpful art introduction to someone visiting Italy for the first time!Specifically, this partial book review will highlight how Jesus Christ was portrayed in Italian Renaissance art, along with any supporting biblical passages.Professor Hartt says that one of the main purposes of the Renaissance was the effort by humanists “to reconcile the ideas they found in Greek and Roman authors with Christian beliefs” (p. 20).CHAPTER 1: PRELUDE – ITALY AND ITALIAN ARTMerchants and GuildsIn the late Middle Ages, most Italian city-states were separate, proud, and independent. They were often at war with each other. They achieved wealth through their merchants. Their governments were dominated by manufacturers, traders, and bankers. Their professions were organized by guilds. There were seven major guilds: 1) Refiners of woolen cloth, 2) Wool merchants who manufactured cloth, 3) Judges and notaries, 4) Bankers and money changers, 5) Silk weavers, 6) Doctors and pharmacists, and 7) Furriers. At first, artists were part of the pharmacists' guild because they had to grind their colors just as pharmacists ground materials for medicines. In 1378, artists became an independent branch within the medical guild. Artists worked on commission and always had a wealthy patron. They learned their craft under a master.AltarpiecesUp until the 13th century, the priest stood behind the altar facing the congregation. When the priest began saying Mass in front of the altar, there was now a great need for painted altarpieces. These depicted Christ or the Virgin Mary or the saint to whom a particular church was dedicated. Patrons began commissioning many images of the Madonna and Child. The dining room in a monastery or nunnery, where the members usually ate in silence, was often decorated with a Last Supper painting.DrawingsBefore a wooden or wall surface was painted, it was first covered with a layer of gesso (finely ground plaster) and glue. Drawings were transferred to the gesso by pricking the drawn lines with a sharp point, then dabbing a porous charcoal bag over them, leaving a row of dots outlining the design. In the early 16th century, drawings were transferred by tracing the metal point of a stylus over the drawn lines. Artists also drew their outlines using a piece of charcoal on a stick, giving them enough distance to see the whole composition as it was drawn.PaintsGold leaf was applied for the background and haloes around the heads. Gold was used because of its beauty and because its luminosity suggested the light of heaven. Tempera paints consisted of ground pigments mixed with egg yoke. Blue pigment was made by grinding azurite from Germany. Ultramarine was made by grinding lapis lazuli from Afghanistan. Both were expensive. By the 15th century, pigments were mixed with linseed oil instead of egg yoke. This made it easier to blend colors, create different thicknesses of paint, and produce greater depth and richness of color.FrescoesFrescoes (Italian for “fresh”) were painted in sections before the surface dried. The wall would be covered with a rough coat of plaster called “arriccio”. The artist first used a brush dipped into a pale, watery earth color that would leave only faint marks. Over these marks, rough outlines of the figures would be lightly drawn in with a stick of charcoal. Then more details were added with a reddish monochromatic painting called a “sinopia”, after the name of the Greek city, Sinope in Asia Minor, the source of the finest red-earth color.GiornatasEach morning the artist would anticipate the area he could paint (called “giornata”) before the fresh plaster dried (called “intonaco”). The joints between each giornata are visible, so today counting the giornata tells how many days the artist took to complete the painting! When the wet paint sank into the intonaco, a chemical reaction took place. The carbon dioxide in the air combined with the calcium hydrate in the plaster, producing calcium carbonate. The colors were now locked into this hardened plaster.SculpturesMost stone sculptures were made with the finest marble found near Carrara, Tuscany. The block of marble would be laid at an incline to afford the sculptor easy access. Outlines were sketched with charcoal on the block, then the sculptor would chip away, first with a pointed and then a toothed chisel. Marks left by the chisel were removed with files. The surface was polished with pumice and straw.BronzeBronze figures were created by carving a figure of clay covered with wax, then covering this with a heat-resistant outer layer of plaster and sand or clay. Heated in a kiln, the wax melted away, leaving a mold into which molten bronze would be poured, cooled, and polished smooth.ArchitectureItalian buildings were inspired by the classical proportions, arches, and decorations of ancient Rome. But their roofs imitated Early Christian basilicas -- flat, wooden ceilings suspended from beams – essentially, large spaces enclosed by flat walls. While under construction, scaffolding consisted of beams inserted in square holes in the outside walls. These square holes were left in the structure so that repairs could be made without rebuilding the scaffolding from the ground up. In a sense, walls are the center of Italian architecture. They form the background for fresco paintings and altarpieces and sculptures. Sadly, the dreams of most Renaissance architects for rebuilding were prevented by war, internal conflict, and lack of funds.BooksIn 1455, Johannes Gutenberg invented movable type (at first wood, later metal). Forty-two lines could be printed all at once, drastically reducing the cost of creating books, which up to that time were handwritten. Books could now be massed produced. The first book he printed was the Bible, in Latin, about 180 copies, of which 48 complete copies survive today. By the end of the 15th century, books were being published in more than 70 Italian towns.Art HistoryThe first historian of Italian Renaissance art was Giorgio Vasari. In 1550, he published “Lives of the Most Eminent Architects, Painters, and Sculptors.”PART ONE: THE LATE MIDDLE AGESCHAPTER 2: 13th CENTURY ART (“DUECENTO”) IN TUSCANY AND ROMEByzantine InfluenceAfter the sacking of Constantinople in 1204 by the Fourth Crusade, artistic works in the Byzantine style were scattered throughout Europe. Byzantine art was characterized by slender figures that were delicately posed. The colors were vivid, yet simple – blue, rose, white, tan, and gold.(School of Pisa. Cross No. 15. Late 12th century (Panel). Artist unknown. Pinacoteca, Pisa)This is a rare presentation of Christ shown alive on the cross. It is called “Christus triumphans” (Christ triumphant). Christ is alive on the cross to show that He is a powerful deity who overcame the torment of the crucifixion.(School of Pisa. Cross No. 20. c.1230. (Parchment on panel). Artist unknown. Pinacoteca, Pisa)This is the common presentation of Christ dead on the cross as “Christus patiens” (suffering Christ), evoking sadness in the viewer. Scenes from the Passion are placed to either side of Christ, in an area called “the apron”, and at the four ends of the cross. A scene of Mary holding her dead son on her lap is not found in the Bible, but this idea was first introduced by the 10th century theologian Simeon Metaphrastes, and is most famously portrayed by Michelangelo's Pieta. Cross 20 is one of the earliest Italian examples of the tragic relationship between the dead Christ and his mother.What changed from an awake Christ on the cross to a suffering Christ? The authors attribute great influence to St. Francis of Assisi who chose a life of simplicity and poverty and who emphasized Christ's suffering for us. The first portrait of St. Francis, occurring nine years after he died, shows him with emaciated cheeks and a piercing gaze, holding the Scriptures, and engaged in meditation and prayer. (Bonaventura Berlinghieri. "St. Francis with Scenes from his Life.” 1235. (Panel). S. Francesco, Pescia)The first named Florentine painter was (Coppo di Marcovaldo. “Crucifix” c.1260s at Pinacoteca, San Gimignano). His “Crucifix” shows Christ's body and face convulsed and distorted. His closed eyes are like two fierce, hooked slashes, while His mouth seems to quiver against the blood-and-sweat-soaked locks of His beard. His hair seems to writhe like snakes against His tormented body. In 1260 after the battle of Montaperti, Coppo was taken prisoner by the Siense after the Florentine defeat. His wartime experiences may have influenced the emotional content of his “Crucifix.”(Coppo di Marcovaldo. “The Last Judgment”1260-1270s. Mosaic. Baptistery, Florence.)This is the most important pictorial project in Florence in the 13th century. The scene is from Matthew 25:31-46. The central figure of Christ is more than 25 feet high. His nail holes are clearly visible. His gaze is fixed on the viewer. The right hand of Christ beckons toward the righteous, while His left hand casts the damned into eternal fire. Hell is a terrifying scene. Satan sits on his throne with horns on his head and snakes coming out of his ears that are devouring people. He is in the process of swallowing a whole person, reminiscent of I Peter 5:8, “the devil prowls around like a roaring lion, seeking someone to devour.” Around him, writhing serpents and monstrous toads devour the damned. Coppo's Christ was the most awe-inspiring representation of divinity in Italian art until Michelangelo.The painter Cenni di Pepi was nicknamed Cimabue. (Cimabue. "Enthroned Madonna and Child with Angels and Prophets” 1280. Panel. Uffizi Gallery, Florence). (The Uffuzi Gallery is a good place to gain an overview of Florentine Renaissance art.) The enthroned Madonna presents her child to the viewer. He holds a scroll and looks directly at the viewer. Angels seem to hold up Mary's throne. Underneath her, Old Testament prophets display scrolls with prophecies of the Virgin Birth.(Cimabue.”Crucifix” 1280s. Panel. Museo di Santa Croce, Florence) Cimabue's “Crucifix” increases the tension of the suffering Christ by showing His arms almost completely stretched out, instead of sagging. This “Crucifix” was damaged in a 1966 flood. There were 56 documented floods, including major ones in 1177, 1333, and 1557, but the one in 1966 was the worst in Florence's history, reaching 20 feet high. The painting was damaged when folding wooden chairs floated up and banged against the surface of the painting.(Cimabue. Fresco. After 1279. Upper Church of St. Francesco, Assisi)The Upper Church is almost completely lined with frescoes. This is the most complete, large-scale cycle of religious imagery in Italy before the Sistine Chapel. Here Cimabue views the Crucifixion as a universal catastrophe. Christ writhes on the cross, His head bent in pain, perhaps already in death. At the foot of the cross to the left are Mary His mother, other holy women, and the apostles. To the right are the Romans, chief priests and elders, and the soldier who declared Christ to be the Son of God.(Nicola Pisano. Pisa Baptistery pulpit. 1260. Baptistery, Pisa)Nicola Pisano's pulpit is a magnificent construction of white Carrara marble, with columns and colonnettes of polished granite and variegated red marble. The baptistery was outside the church in a separate building because people could not enter a church until they were baptized. In one relief panel, the Angel Gabriel announces to the Virgin Mary that she will be the mother of the son of God. According to theologians, when Gabriel's words struck her ear, the human body of Christ was conceived in her womb.Nicola's son, Giovanni Pisano, designed the lower half of Sienna's Cathedral. The black-and-white striping of the exterior and interior matches the coat of arms of Sienna. The cathedral was built with white marble from Carrara and dark green marble from Prato. Giovanni also helped his father complete a large pulpit (Giovanni Pisano. Pulpit. 1298-1301. Sant' Andrea, Pistoia) Giovanni carved an inscription which begins with praise to God, “In praise of the triune God I link the beginning with the end of this task in thirteen hundred and one”, and ends with self-congratulations, "Giovanni carved it, who performed no empty work. The son of Nicola and blessed with higher skill.”(Giovanni Pisano. “Massacre of the Innocents”. 1298-1301. Marble panel on the Pistoia pulpit)Giovanni carved the scene in Matthew Chapter 2 of the slaughter of children under the age of two. King Herod had commanded this in an attempt to kill Jesus whom he feared would usurp his throne. As Herod gives the order, the scene is filled with wailing mothers, screaming children, and violent, sword-wielding soldiers. Mothers are cradling their dead babies. Sibyls are shown sharing in the agitation, as it was believed that even Greek and Roman prophetesses foretold the coming of Christ. Later, Michelangelo would include them in his Sistine Chapel.CHAPTER 3: EARLY 14th CENTURY ART (“TRECENTO”) IN FLORENCEThe emergence of a new painter, Giotto di Bondone replaced the Byzantine style of Cimabue. (Giotto. Fresco style. c.1302-1305. Arena Chapel, Padua) The Arena Chapel frescoes represent Giotto's greatest achievement. Their state of preservation is astonishing, given that an Allied bomb narrowly missed the chapel during WWII. Thirty-eight framed scenes tell the story in sequence of the Virgin (Panels 1-15) and Jesus Christ (Panels 16-38). Panel #1 begins with the story of Joachim and Anna, who are the parents of Mary (the mother of Jesus) according to the apocryphal Gospel of James. Panel #38 shows the coming of the Holy Spirit at Pentecost. Highlights include the Marriage of Mary and Joseph (#11), the Annunciation (#14A&14B), the Nativity (#16), the Adoration of the Magi (#17), the Baptism of Christ (#22), the Raising of Lazarus (#24), the Last Supper (#28), the Crucifixion (#34), the Resurrection (#36), the Ascension of Christ (#37). The Last Judgment covers the entire entrance wall.In panel #16 of the Nativity and Annunciation to the Shepherds, Giotto paints a midwife handing the Christ Child, already washed and wrapped, to Mary, while an ox and donkey look on, in fulfillment of the Old Testament prophecy in Isaiah 1:3 “An ox knows its owner, and a donkey its master's manger...”In The Last Judgment, angels roll away the sun, the moon, and the heavens like a scroll (Isaiah 34:4 and Revelation 6:14), revealing the golden gates of paradise. In the center of the wall, Christ appears as judge. Unlike Coppo's terrifying judge who stares impassively, Giotto's compassionate Christ averts His face from the damned. The explicit physical torment suffered by some of the sinners is unforgettable. A monk is hung by his tongue while the woman next to him is suspended by her hair. One figure is being turned on a spit, while a trussed woman has hot lead poured into her mouth. A devil uses tongs to squeeze the penis of one sinner. Rivers of red and orange fire flow from the throne of Christ to engulf the damned.CHAPTER 4: EARLY 14th CENTURY ART (“TRECENTO”) IN SIENAThe foremost painter in Siena was Duccio di Buoninsegna. Mary, the mother of God, was Siena's patron saint who they believed protected their city. Duccio painted an enormous altar piece called (Duccio. "Maesta”, Virgin in Majesty. 1308-11.Panel.Siena Cathedral). Biblical scenes were often painted in the context of the painter's current location and time period. Scene #11, The Temptation of Christ on the Mountain, shows Satan tempting Christ with the kingdoms of the world. Duccio paints the kingdoms as Italian city-states with walls and gates surrounding public and religious buildings with towers, domes, roof tiles, and battlements. In scene #18, Entry into Jerusalem, Christ rides upon a donkey in fulfillment of Zechariah: “Behold, your King is coming to you...humble, and mounted on a donkey.” The setting looks like a crowded medieval city instead of ancient Jerusalem.In scene #35, the Crucifixion, Duccio shows the legs of the two thieves broken but Christ's legs are intact, fulfilling a prophecy that “not a bone of Him shall be broken” (John 19:36 and Psalm 34:20). Just as the Passover lamb's bones were not to be broken (Exodus 12:46), so Christ as our Passover Lamb had no broken bones. Mary His mother swoons below the cross, sinking into the arms of the holy women as she looks up toward her son, from whose side blood and water gush in streams.The earliest known example in which the Annunciation was the subject of an entire altarpiece was painted by Simone Martini. (Simone Martini and Lippo Memmi. “Annunciation with Two Saints.” 1333.Panel.Uffizi Gallery, Florence). The breathless arrival of the angel Gabriel is indicated by the cloak that floats behind him. His announcement of Luke 1:28, “Hail, thou that art highly favored, the Lord is with thee” stretches from his mouth to Mary's ear in raised gesso words in beautiful Gothic lettering. Mary shrinks back sharply at the news, following Luke 1:29 that she was “very perplexed at this statement.” The angel told her to “not be afraid, Mary; for you have found favor with God.”New Testament frescoes on the right side-aisle wall of the (Collegiate Church in San Gimignano are attributed to either the workshop or followers of Simone Martini.1330s or 1340s). Among the scenes is “The Pact of Judas” showing the moment the high priests give Judas 30 pieces of silver to betray Christ. The heads of the priests form a human arch. The perspective of the architecture seems to pull us into the scene, suggesting our guilty complicity in the betrayal.Another scene is “The Betrayal”, where Christ is never more alone as His apostles leave Him to His fate. The young John gathers his cloak about him and darts a look of terror over his shoulder as he hurries away. Christ seems to have been abandoned to an avalanche of steel. His quiet face resists Judas' glare even as He is cut off from the rest of the world. This painting offers an individualized and pessimistic view of human behavior that is unforgettable.(Pietro Lorenzetti. Fresco. “Descent from the Cross.” 1320s-30s.Lower Church of Saint Francesco, Assisi). The gaunt body of Christ, the effects of rigor mortis indicated in its harsh lines and angles, is lowered by His friends. Joseph of Arimathea holds the torso while St. John embraces the legs, pressing his cheek to one thigh. Nicodemus, holding an immense pair of tongs, attempts to withdraw the spike from one pierced foot while Mary Magdalen prostrates herself to kiss the other. Mary, the wife of Clopas, holds Christ's right hand, and Mary, Christ's mother, presses His head to her cheek in a way that unites the two heads, one right side up, the other upside down.(Ambrogio Lorenzetti. "Presentation in the Temple.” 1342. Panel. Uffizi Gallery, Florence)Ambrogio precisely illustrates Luke 2:22-38. The offering of two turtledoves can be seen on the altar. The aged Simeon, who has been told that he would not die until he had seen the Messiah, holds the Christ Child and murmurs the words of “Nunc Dimittis”: “Now Lord, You are releasing Your bond-servant to depart in peace, according to Your word; for my eyes have seen Your salvation, which You have prepared in the presence of all peoples, a light of revelation to the Gentiles, and the glory of Your people Israel” (Luke 2:29-32). At the left stand Joseph, Mary, and two attendants. On the right, the 84-year-old prophetess Anna holds a scroll with Luke 2:38 “At that very moment she came up and began giving thanks to God, and continued to speak of Him to all those who were looking for the redemption of Jerusalem.” Ambrogio depicts differences in age and feelings, from the Christ Child blissfully sucking His thumb and the gentle pride of His mother to the wrinkled Anna and the weariness of Simeon, who will now be released from the burden of life.CHAPTER 5: LATER GOTHIC ART IN TUSCANY AND NORTHERN ITALYDuring the 1330s and 1340s, calamities struck Florence and Siena. There was a flood in 1333, bank failures in the mid-1340s, famine in 1346-7 from agricultural disasters, and the bubonic plague in 1340, and much worse in 1348. Art reflected the changes that came from a wave of guilt and self-blame following catastrophes. Religion explained catastrophe as divine wrath while at the same time offered comfort in the belief of eternal life.(Giovanni Da Milano. “Pieta”. 1365. Panel. Accademia, Florence). The deceased Christ is upheld by His mother, Mary Magdalen, and St. John. The manner in which Christ's body is raised by the grieving figures is intended to remind the observer of the suffering Christ endured for humanity. The intense emotion of pictures such as this reminds us of how art served religion during this period, as an aid to personal devotion. The absence of any setting and the luminous gold background focus the worshipper's attention on the inner meaning of Christ's sacrifice. The Pieta became an important theme in Italian art, and was chosen by both Titian and Michelangelo for their own tombs.(Lorenzo Monaco. “Nativity”, on the predella of “The Coronation of the Virgin.” 1414. Panel. Santa Maria degli Angeli, Florence). Lorenzo's “Nativity” is partly based on the writings of St. Bridget, a 14th-century Swedish princess who had a vision at the cave in Bethlehem that traditionally marks the site of the Nativity. The Adoration of the Child became a new version of the Nativity in 15th century Florence. In Lorenzo's scene, Mary kneels to worship her newborn child, who is surrounded by golden rays. In her vision, Bridget said that light radiated from the newborn child.NORTHERN ITALYVenice – A Brief HistoryFounded in 5th and 6th centuries on marshy islets by refugees from the Roman cities of the Po Valley who were fleeing invaders. They chose the superiority of its lagoons over land-based fortifications for its security. It was the only state in Western Europe to survive from antiquity to modern times without revolution, invasion, or conquest (until Napoleon). Its navy was vast. It relied upon sea commerce by taking over ports down the Adriatic coast, the Greek islands, and one-fourth of Constantinople after its capture by Crusaders in 1204. The colorful pageantry of Venetian art comes from its topography, ships, flags, exotic spices and silks brought from many nations, palaces of brick, limestone, and marble. The Franciscan church of Santa Maria Gloriosa dei Frari and the Dominican Church of Santi Giovanni were made of brick, a lighter material than stone. Both are made in the form of a cross (“cruciform”), with Gothic ribbed cross-vaults and wooden tie-rods to constrain the outward thrusting of the vaulting, thus avoiding heavy buttressing on the exterior. The supporting piers are enormous cylinders. The massive scale satisfied the need for large preaching spaces for the standing congregations, while the austerity of design and lack of decoration conveyed simplicity of both the Franciscans and the Dominicans.Altichiero from Verona(Alticheiro.“Crucifixion.”1375. Fresco. Chapel of St. Felix (formerly St. James), Sant'Antonio, Padua). One of the largest and most impressive frescoes of the 14th century. The columns that divide the scene repeat the arched colonade that separates the chapel from the nave, making us feel as if we are viewing the crucifixion through them, giving it a greater vivacity.(The Milan Cathedral. Begun 1385 or 1385. Construction took several centuries). Debates occurred about its design. At one point, the participants were divided into two camps. One emphasized practical engineering experience, at that time called “ars” (art). The other emphasized “scientia” (science), which meant a dependence upon geometric ordering and design, arguing that without geometry, the engineering is nothing. The first group capitulated, agreeing that no architect could ignore the primary importance of geometry in design and construction. The idea that there is an intimate connection between architecture and mathematics reflects St. Augustine's “De Musica” (387-89), in which he said that the mathematical proportions necessary for both music and architecture were the same as those of the universe. He said these disciplines thus aided us in contemplating the divine order of God's creation.PART TWO: THE QUATTROCENTO (15th Century)CHAPTER 6: THE RENAISSANCE BEGINS – ARCHITECTURE(Filippo Brunelleschi. Dome.1420-1436. Santa Maria del Fiore Cathedral, Florence).What made Brunelleschi's dome one of the greatest architectural achievements was how he constructed it without using a supporting structure, which would have required a whole forest of trees! Several engineering marvels give the dome its strength. First, there are 8 visible vertical ribs, and 16 more hidden ones, for a total of 24 vertical ribs. These join with 9 horizontal ribs to give the dome its skeletal structure. Secondly, the outward thrust of the dome, the tendency for the dome walls to push outward, is contained by 4 stone chains and one wooden chain that encircle the dome. And thirdly, the bricks were laid in a herringbone pattern, with vertical bricks laid next to a row of horizontal bricks. The vertical bricks acted like “book ends”, applying pressure on the horizontal bricks, and thus resisted the tendency for gravity to pull them inward toward collapse. Brunelleschi also invented an oxen-driven hoist to lift the bricks and mortar up to the masons, who otherwise would have had to carry them on their shoulders up long stairways.(Filippo Brunelleschi. “Ospedale degli Innocenti” Hospital of the Innocents. Begun 1419. Piazza della SS. Annunziata, Florence.) This provided orphans and abandoned children with housing, education, and vocational training until the age of eighteen. These children were given the last name Innocenti. The role of this hospital in Florentine history is revealed by the large number of citizens today who still bear this name. The building's exterior arches are adorned with terra-cotta medallions by Andrea della Robbia (1487) which represent infants wrapped in swaddling clothes as a reference to the “Innocents killed by the order of King Herod” (Matthew 2:16). In determining measurements for his arches, doors, windows, and columns, Brunelleschi relied upon a system of proportions developed by the 6th-century Pythagoras, who had noted that when a stretched string is plucked, it vibrates to produce a note, and that when the string is measured and plucked at points that correspond to exact divisions by whole numbers – such as ½, 1/3, ¼ – the vibrations will produce a harmonious cord. Brunelleschi followed in the footsteps of St. Augustine, who drew connections between mathematics, music, and architecture, relating all three to the harmony of God's universe. The Florentine humanist Giannozzo Manetti stated in his book “On the Dignity and Excellency of Man” that the truths of the Christian religion are as clear and self-evident as the axioms of mathematics. The rational, ordered clarity of Brunelleschi's religious buildings support the Florentine humanist idea that geometric principles could unlock the mysteries at the heart of the universe and reveal the intentions of a God who was eminently understandable and had created the universe for human enjoyment.CHAPTER 7: TRANSITIONS IN TUSCAN SCULPTURE(Lorenzo Ghiberti. Bronze Doors. 1403-24. Baptistery, Florence)In 1401, Lorenzo Ghiberti won a contest to decorate the doors of the Florentine Baptistery. His panel and Brunelleschi's panel of Abraham's Sacrifice of Isaac (Genesis 22:1-12) are preserved in the Museo Nazionale del Bargello in Florence. Abraham, accompanied by two servants and a donkey, took Isaac into the wilderness, but just as he held the knife to his son's throat, God sent an angel to tell him that the Lord was pleased by his faith and would be satisfied with the offering of a ram caught in a nearby thicket. The story was interpreted as a foreshadowing the sacrifice of Christ. Brunelleschi's relief is full of action poses. Abraham twists Isaac's head to expose his neck while the angel has to rush in and physically restrain Abraham. His brutal treatment of Isaac suggests that he has to suppress the knowledge that he is about to sacrifice his only child. In Lorenzo's panel, Isaac looks upward for deliverance. Abraham, his arm embracing the boy, is poised with his knife pointed toward but not touching his son. The foreshortened angel stops the sacrifice with a gesture. The ram rests quietly in the thicket, while the servants converse gently.CHAPTER 8: TRANSITIONS IN FLORENCE PAINTING(Masolino, Masaccio, and Filippino Lippi. 1420s. Fresco style. Brancacci Chapel. Santa Maria del Carmine, Florence). A rare painting of the biblical story in Matthew 17:24-27 where Christ tells Peter to go throw a hook into the sea, and the first fish that comes up will have a shekel inside by which Peter can pay the annual temple tax required of every male 20 years of age and older. The annual tax of half a shekel would pay for both Jesus and Peter.